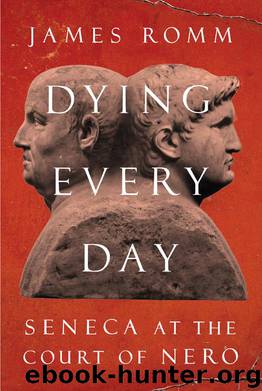

Dying Every Day by James Romm

Author:James Romm

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

ISBN: 9780385351720

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2014-03-10T22:00:00+00:00

Unable to resign even at the price of his huge estate, Seneca had nonetheless withdrawn from court to the degree that was safe. He no longer kept up the routine of a powerful statesman, no longer saw crowds of clientelae, friends in need of favors, in his chambers each morning. He rarely went out in public, and when he did, he no longer had a large retinue of attendants. He was trying, within the limits Nero had set, to reduce his visibility.

His pace of writing increased. He had more time now for moral reflections and a greater need to publish them, for his reputation had suffered badly as Nero had spiraled downward. From 62 on, he produced an astounding body of work, some of it now lost, much still extant. His longest and most ambitious prose works were composed at this time and, almost certainly, his most harrowing tragedy, Thyestes. Seneca, now at the peak of his literary powers, was writing like a man running out of time—as indeed he was.

Seneca was in his midsixties and feeling his age. Constantly cold, depleted by lifelong respiratory disease, he claimed to be “among the decrepit and those brushing up against the end.” Everywhere he looked, he saw reminders that he had passed into the last phase of life, his senectus. Making the rounds of his estates, he found that a stand of plane trees had become gnarled and withered; he scolded a caretaker for failing to irrigate them. The man protested that the trees were simply too old to be helped. Seneca did not reveal to the caretaker, but did to his readers, that he himself, in youth, had planted those trees.

Seneca was often on the move, whether checking on his properties or following the emperor and the court through Italy. He was in Campania much of the time, sometimes visiting the wealthy resort towns of Baiae and Puteoli. He went at least once to Pompeii, as he eagerly wrote to his old friend Lucilius, a native of that town. Seneca felt closer to Lucilius as the years advanced, perhaps because so many other friends were dead. A man slightly younger than Seneca, a fellow member of Nero’s staff—caretaker of the emperor’s estates in Sicily—Lucilius shared Seneca’s literary tastes and philosophic concerns. He was also a fellow survivor, having undergone torture at the hands of Messalina and Narcissus, Seneca’s persecutors as well.

Wherever Seneca went in these years, he carried on work on his magnum opus, a remarkable set of short moral essays framed as letters. Ostensibly addressed to Lucilius, these letters were in fact aimed at a wide audience. But the fiction of an intimate correspondence gave Seneca latitude in the structure of the essays, as well as unusual freedom to vary voice, tone, and technique. The melding of ethical inquiry with epistolary style produced a breakthrough for Seneca. He carried on the Letters to Lucilius at far greater length than anything else he had written and with greater candor about his life and thoughts—or at least, what seems to be candor.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| France | Germany |

| Great Britain | Greece |

| Italy | Rome |

| Russia | Spain & Portugal |

Fanny Burney by Claire Harman(26581)

Empire of the Sikhs by Patwant Singh(23057)

Out of India by Michael Foss(16837)

Leonardo da Vinci by Walter Isaacson(13288)

Small Great Things by Jodi Picoult(7099)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5483)

The Wind in My Hair by Masih Alinejad(5069)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

The Crown by Robert Lacey(4784)

The Lonely City by Olivia Laing(4783)

Millionaire: The Philanderer, Gambler, and Duelist Who Invented Modern Finance by Janet Gleeson(4446)

The Iron Duke by The Iron Duke(4334)

Papillon (English) by Henri Charrière(4238)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4169)

Joan of Arc by Mary Gordon(4076)

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read(4009)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3937)

Aleister Crowley: The Biography by Tobias Churton(3621)

Ants Among Elephants by Sujatha Gidla(3449)